I am always looking and listening for nature when I’m out walking. Yesterday was a wet day (we’ve had a week of rain here in Montenegro), and in the absence of birds and flowers my eyes were drawn to the abundance of lichens that we saw on the trails.

Lichens are a partnership between a fungus and either an alga or type of bacteria called cyanobacterium. The fungus provides structure and protection, while the photosynthetic partner produces food. This symbiotic relationship allows lichens to thrive in some of the most extreme environments on Earth. While I've seen these survivors in Antarctica, the Sahara Desert, and atop mountains in the Himalayas, the diversity found right here in the Montenegrin beech forests is staggering. Wherever I guide, even on those quiet nature days, I know that there will be a lichen nearby which I can enthusiastically discuss (as a guest smiles politely and reconsiders the character of their guide).

Montenegro's forests and mountains are home to an abundance of healthy lichen populations, and while hiking yesterday many of the branches were covered in lichen. Certain lichens are highly sensitive to air pollution, and so the lichens that I saw out on the hill were a sign of clean, unpolluted air—some of the purest in Europe.

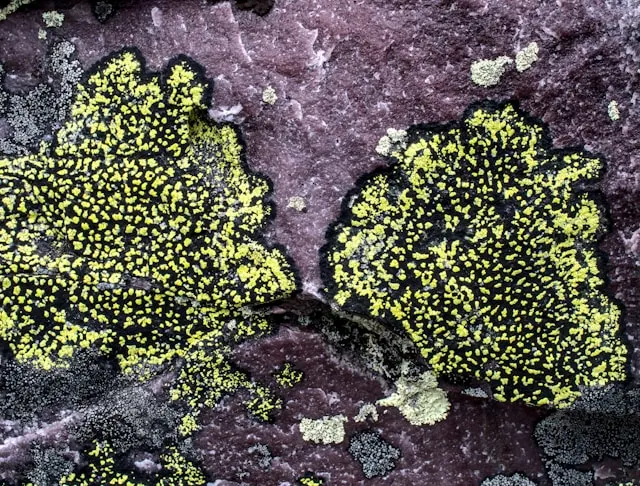

Another reason lichens stood out so much during my hike was that the rain changed their appearance. When wet, the fungal cells within the lichen became more translucent, revealing the colors of their photosynthetic partners. Lichens with bright green or yellow hues are usually dominated by algae, while darker green or brown lichens often contain cyanobacteria.

There are many lichens to see in wild places, but even living within urban areas we all have the opportunity to see lichens on a daily basis. So how do we spot them? A good place to start is to try and identify each of the 3 different groups.

Quick Guide to Lichen Types

| Lichen Type | Look For... | Where to Find in the Balkans |

|---|---|---|

| Crustose | Flat "paint splatters" on rocks | Limestone peaks in Durmitor and Orjen |

| Foliose | Leafy, peeling layers | Bright yellows on old wooden fences and tree bark |

| Fruticose | Tiny shrubs or "old man's beard" | Hanging from pines in Biogradska Gora |

Crustose Lichens, unsurprisingly, are a crust. They cannot be removed from their substrate, which is the surface that they grow on. Most crustose lichens are far less sensitive to air pollution than the other types, and as a result these coloured patches can be found in cities and urban areas. Crustose lichens grow very slowly (0.1 - 2mm per year), and have given birth to the science of lichenometry, which is a method for dating the age of exposed rocks based on the growth rates of the lichens that are on them.

Foliose Lichens. Folio means leaf like in latin, and these leaf-shaped lichens are attached to their substrate at one point. Many foliose (and fruticose) lichens are highly sensitive to air pollution, particularly sulfur dioxide, making them excellent bioindicators for environmental health.

Fruticose Lichens have a branching, shrub-like structure, and are often found hanging from trees or growing upright on rock. They have a three-dimensional structure, and grow on but not attached to their substrate. Many fruticose lichens, such as the Cladonia species below, are rich in ascorbic acid and have antimicrobial propeties, which is why they are used in some traditional medicines for treating colds and disinfecting wounds.

See Lichens on a Guided Trek

On our guided tours through the Orjen and Durmitor ranges, we don't just hike for the views; we stop to look at the stories written on the rocks. From the vibrant orange crustose lichens painting ancient limestone to the delicate "old man's beard" hanging from century-old pines, these organisms reveal the health of Montenegro's pristine mountain ecosystems.

If you're interested in exploring Montenegro's trails with a guide who can point out not just the peaks but the fascinating details along the way, join me on a trek.

So on your next hike or city walk, slow down and look closely—you might just uncover the hidden world of lichens.

📸 Tag me in your lichen photos on IG @hikebalkans.